Reflections on Waterfall, Agile, and Requirements - Part 1

I remember sitting in a lecture theatre not too long ago, and being told that 68% of software projects fail . “This is clearly a joke” I thought, “designed to suck us into the next topic we’ll be examined on. How is it that software is ever delivered? How much potential are we losing out on by letting this happen?”.

Fast-forward to the present, and I’m finally beginning to appreciate the values of agile. My requirements are changing on a (no joke) daily basis, which typically involves revisiting a 60-page design document, making changes, updating the associated Swagger specifications (since we’re developing a bunch of APIs), and getting the whole lot approved by the client (yada yada yada typical waterfall stuff). While waiting for at least a business day for this to happen, we’ve taken on the risk of “building ahead” by implementing the unapproved changes in code and crossing our fingers. It’s a nightmarish situation where you have an elephant in the room (the design docs) in constant need of pampering by people whose time are better spent building software.

Every time a change is requested, we increment the version number of the document. Every time we send out an updated version of the document, it becomes obsolete again. Well written software coupled with tests that demonstrate behaviour in all scenarios is the best documentation you can produce.

The difference between an agile project and a waterfall one is the volume of outdated documentation that’ll end up on your hands. Both methodologies advocate the importance of requirements gathering in one form of another, with different levels of leniency in getting the whole lot right in the beginning. Two of the four values stated in the Agile Manifesto clearly reflect on the fruitlessness of defining requirements that are accurate to the T:

Working software over comprehensive documentation

Responding to change over following a plan

This doesn’t imply that clear requirements are completely out of the picture in an agile project however. We want working software, which means we need good quality requirements of some form to satisfy the intention at that point in time, and we also want to respond to change by taking on board new requirements as they come about.

The waterfall model places a heavy emphasis on getting it right from the get-go; a formidable goal if not working against how we as humans operate (and by the way, software engineering is still inherently a human task).

A great article entitled the Planning Fallacy refers to a psychological study conducted in the mid-90s which highlighted the challenges we face in planning, even if those plans are rooted on the basis of past experience.

While it might be sensible for some projects to align with this model (think low-level systems like avionics for an aircraft) where the outcome should be clearly defined for the the sake of arriving alive at the expense of delays and cost overruns, the majority of software benefits from maximum flexibility in the delivery phase. The idea that one must know every little detail of how something will operate before an attempt can be made to build it is mind boggling in most cases.

So what’s the trick then? Define an minimum delightful experience!

There’s a good analogy which the UX designers use where I work to separate the various stages of software maturity. Stage 1 starts with a cupcake that’s in sharp focus; knowing exactly what ingredients will go in, how it’ll be made, what it’ll look like, and how it’ll taste. Stage 2 moves to a fuzzy birthday cake; with a design and feature set we think we’ll have. Stage 3 defines a blurry wedding cake; something we might get to depending on how the first two stages work out.

The purpose of an M_D_P (emphasis on delightful) is to showcase a vertical slice of what your software may one day become.

You can visualise this in the form of a slice of pizza; a vertical slice encompasses a bit of crust, topping, and base, while minimum viability could mean a horizontal slice of crust.

This helps the humans consuming your software to get a complete feel of the direction it’s taking, so any changes to the requirements down the track can largely be foreseen and rationalised (imagine baking a pizza crust only to find out the customer wants sauce, cheese, and toppings!). A properly executed MDP is also itself a usable piece of software. It may not do everything the person has in mind, but it does enough to demonstrate capability.

If you were building a chatbot, an MDP might consist of a nice UI on a website, the ability to answer basic questions, and to functionality to store contextual information like the user’s name. As you progress to Stages 2 and 3, additional features like a responsive mobile UI (or native app), more complex questions involving back-and-forth interaction with the user, and the ability to extract data from historical interactions to form a user profile can be investigated.

This end-to-end capability, no matter how thin the slice, must make its way to the people using the software as quickly as possible. It’s only by playing around and breaking things that people realise how the reality has matched their expectations.

Sidenote: There’s a lot of misconception out there of what chatbots are capable of, considering the major vendors of such software slap terms like AI, and “virtual agent” on top of what is essentially conditional logic. The real power of a chatbot comes from the natural language processing used to determine the true intent of the user’s question. The answers that are generated are mostly hard-coded and no more personalised than clicking through graphical menus.

Managing expectations is tough, and there’s no foolproof formula to getting it right (otherwise BAs would be out of a job and marketing would be the practice of telling the truth!). The best thing to do is encourage ourselves to start small (not matter how trivial the task) and work up from there.

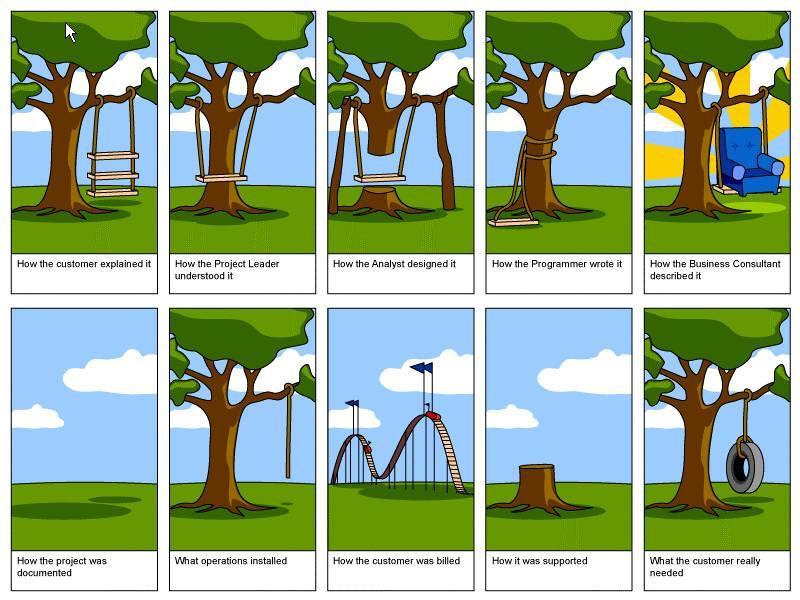

The classic illustration of how expectations are managed

The classic illustration of how expectations are managed

What happens when the requirements and expectations aren’t clear? In the next part we’ll see from the relatively safe perspective of a Stackoverflow question.