Generating Salads

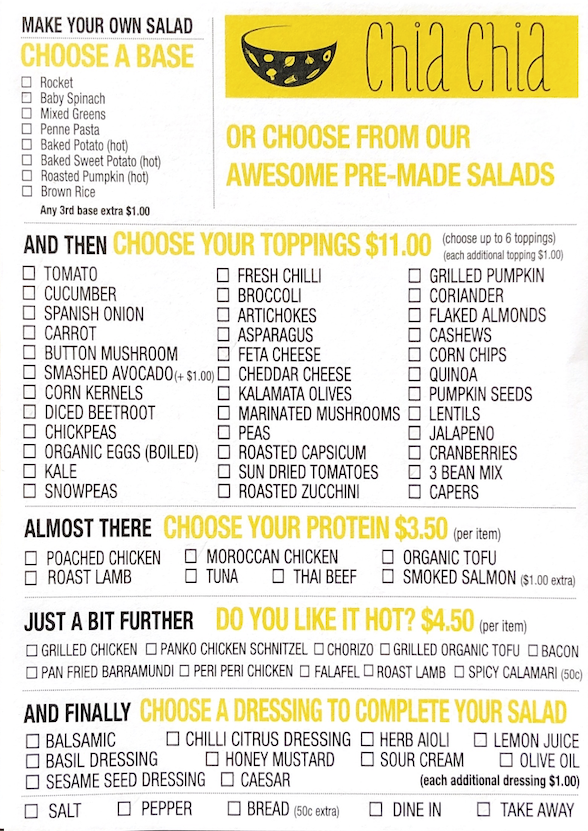

There’s a salad place I like called Chia Chia near where I’m currently working. I like it for the same reasons I hate it; it epitomises my fear of choice. How so? Here’s their salad “menu”:

Scary isn’t it? There are 100 possible combinations of bases alone! Maybe trying out all of the salads here will make it into the bucket list. It’ll certainly be quite a gastronomical achievement.

Of course, there are “better” things for a bucket list and trying every possible combination of ingredients would likely produce more than a few inedible salads. We should find a smarter way, using computers and algorithms! In additional to saving our wallets and tastebuds, this will sure to be a fun filled adventure in programming. Here’s what I’m thinking:

- ingredients by themselves are somewhat difficult to reason with; does

tomatogo well with3 bean mix? Who knows. If I choose abrown ricebase, how awful would acaeserdressing be? - abstractions of ingredients might be the way.

- an abstraction of an ingredient for this purpose would be the feeling, visual property, or dominant flavour of the ingredient. For instance,

Lemon Juice,Balsamic, andSun Dried Tomatoesmight all be implementations of anacidicabstraction, while agreensabstraction could encapsulate things likecucumber,broccoli, andbasil dressing. - an ingredient can be an implementation of one or more abstraction, perhaps with an attached weight.

- when setting the parameters for the salad generator, I should only have to reason with abstractions and their amounts and combinations.

- an inedible salad should never be generated.

Abstracting ingredients#

When we talk about abstracting ingredients, our goal is to identify an overarching feeling, visual property, or dominant flavour of the ingredient. My favourite cookbook (also the only one I have ever read), describes flavour as lying “in the intersection of taste, aroma, and sensory elements including texture, sound, appearance, and temperature”, where aroma is any of thousands of chemical compounds sensed by our noses, and taste is the saltiness, sourness, bitterness, sweetness, and umami perceived by our tastebuds.

For each ingredient on the menu, we want to encode its flavour in a way that is deep enough for the user to select without much thought, but shallow enough that relations can be made to neighbouring encodings. There exists a concept called flavour pairing which considers that 80% of the reason why something tastes nice is due to its aroma versus its taste (we have 5-10 million smell receptors as opposed to about 9000 tastebuds), and looks at the molecular similarity between ingredients to recommend suitable pairings. FlavourDB is a tool we can use to explore these flavour molecules. There’s no API, but data on ingredients are available to download as JSON files.

Here’s a sample of the JSON representation of a tomato:

{

"category": "vegetable-fruit",

"entity_id": 364,

"category_readable": "Vegetable Fruit",

"entity_alias_basket": "tomato, tomato-juice, tomato-paste, tomato-puree",

"entity_alias_readable": "Tomato",

"natural_source_name": "Solanum",

"entity_alias": "tomato",

"molecules": [

{

"bond_stereo_count": 0,

"undefined_atom_stereocenter_count": 0,

"taste": "",

"functional_groups": "carboxylic acid derivative@carboxylic acid ester",

"fooddb_flavor_profile": "hop_oil@apricot@whiskey@banana@tropica@papaya@melon@fruity@pear@green",

"supersweetdb_id": "",

"fema_number": "2060",

"fooddb_id": "FDB019935",

"common_name": "Isoamyl butyrate",

"hba_count": 2,

"synthetic": 0,

"isotope_atom_count": 0,

"bitterdb_id": "",

"covalently_bonded_unit_count": 1,

"molecular_weight": 158.241,

"super_sweet": "",

"charge": 0,

"flavornet_id": 0,

"fenoroli_and_os": 1,

"exact_mass": 158.131,

"pubchem_id": 7795,

"bitter": 0,

"iupac_name": "3-methylbutyl butanoate",

"volume3d": "137.5",

"unknown_natural": 0,

"odor": "",

"num_rotatablebonds": 6,

"smile": "CCCC(=O)OCCC(C)C",

"inchi": "InChI=1S/C9H18O2/c1-4-5-9(10)11-7-6-8(2)3/h8H,4-7H2,1-3H3",

"undefined_bond_stereocenter_count": 0,

"defined_bond_stereocenter_count": 0,

"xlogp": "2.6",

"topological_polor_surfacearea": 26.3,

"cas_id": "106-27-4",

"natural": 1,

"flavor_profile": "hop_oil@apricot@whiskey@banana@tropica@papaya@melon@fruity@pear@green",

"hbd_count": 0,

"fema_flavor_profile": "Fruit",

"complexity": 108.0,

"heavy_atom_count": 11,

"defined_atom_stereocenter_count": 0,

"monoisotopic_mass": 158.131,

"atom_stereo_count": 0

},

{

"bond_stereo_count": 0,

"undefined_atom_stereocenter_count": 0,

"taste": "",

"functional_groups": "carboxylic acid derivative@carboxylic acid ester",

"fooddb_flavor_profile": "peach@vegetable@herbal@apple peel@fresh@cut grass@fruity",

"supersweetdb_id": "",

"fema_number": "2572",

"fooddb_id": "FDB011707",

"common_name": "Hexyl Hexanoate",

"hba_count": 2,

"synthetic": 0,

"isotope_atom_count": 0,

"bitterdb_id": "",

"covalently_bonded_unit_count": 1,

"molecular_weight": 200.322,

"super_sweet": "",

"charge": 0,

"flavornet_id": 1,

"fenoroli_and_os": 1,

"exact_mass": 200.178,

"pubchem_id": 22873,

"bitter": 0,

"iupac_name": "hexyl hexanoate",

"volume3d": "177.4",

"unknown_natural": 0,

"odor": "",

"num_rotatablebonds": 10,

"smile": "CCCCCCOC(=O)CCCCC",

"inchi": "InChI=1S/C12H24O2/c1-3-5-7-9-11-14-12(13)10-8-6-4-2/h3-11H2,1-2H3",

"undefined_bond_stereocenter_count": 0,

"defined_bond_stereocenter_count": 0,

"xlogp": "4.4",

"topological_polor_surfacearea": 26.3,

"cas_id": "6378-65-0",

"natural": 1,

"flavor_profile": "peach@vegetable@herbal@apple peel@fresh@cut grass@fruity",

"hbd_count": 0,

"fema_flavor_profile": "Apple Peel, Peach, Plum",

"complexity": 132.0,

"heavy_atom_count": 14,

"defined_atom_stereocenter_count": 0,

"monoisotopic_mass": 200.178,

"atom_stereo_count": 0

}

]

}

There’s a heap of properties we don’t really care about, such as atom_stereo_count and inchi. Perhaps in a different life these would make sense, but certainly not now. What we’re probably interested in is the flavour_profile property of each molecule object, an @-separated list of flavours we can unpack and rank. We can create a hashmap of flavours and their counts, take the top x% of flavours, and begin to establish relationships between the ingredient and the flavour. We should keep track of the molecule too which may aid in matching – pubchem_id seems like a good candidate to use as an ID.

For example, we might end up with this after examining all of the molecules in tomato:

"tomato": {

"flavour_profiles": [

{

"name": "sour",

"molecules": [8314, 11552, 802]

},

{

"name": "acid",

"molecules": [8314, 61503]

}

]

}

In this representation, we capture a ranked array of flavour profiles along with associated molecule IDs. We can then easily make comparisons with other ingredients to form pairs, while presenting the abstracted flavour profile name to the user.

Data Model#

Chia Chia segment the menu into bases, toppings, proteins, dressings, and condiments/extras. The generator should respect these categories and account for the differing impacts of each type of ingredient to the overall taste of the salad. On top of this, we proposed abstracting each ingredient to one or more flavour profiles and establishing relationships between these abstractions. There are also metadata like price which should be stored.

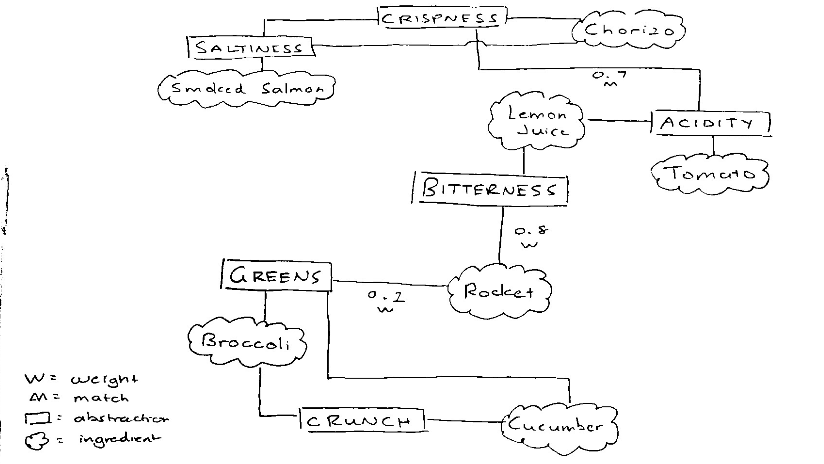

We can sketch out a rough draft of the data objects and their relations like so:

This is beginning to resemble a familiar data structure – graphs! We have ingredients and their abstractions as vertices, and edges to represent well-matching flavours. Adjacent vertices with a strongly weighted edge are flavour profiles which are well-suited to be combined, or based on the user’s selections. We can establish high-level relationships amongst flavour profiles, with each flavour profile vertex branching off to one or more ingredients using the same weighting scheme discussed earlier. Another element to consider is the different categories the ingredients fall into (bases, proteins, dressings etc.). Our walk through the graph must encomposs the correct number of each type of ingredient, but not necessarily in a specific order.

Let’s review the constraints:

- ingredients are children of one or more flavour profiles, with weightings of how closely they associate with the flavour. The upper limit of flavour profiles per ingredient is determined by the sum of all weights, which must <= 1.

- ingredients are members of a category, which together can be composed into a salad.

- at least one ingredient from each category should be selected.

- there is no order to the way the ingredients need to be chosen.

- flavour profiles can relate well (high weight) or poorly (low weight). This weighting is determined through two factors:

- user selection – which flavour profiles do they want most in the salad?

- static values – how well do the flavour profiles combine in general?